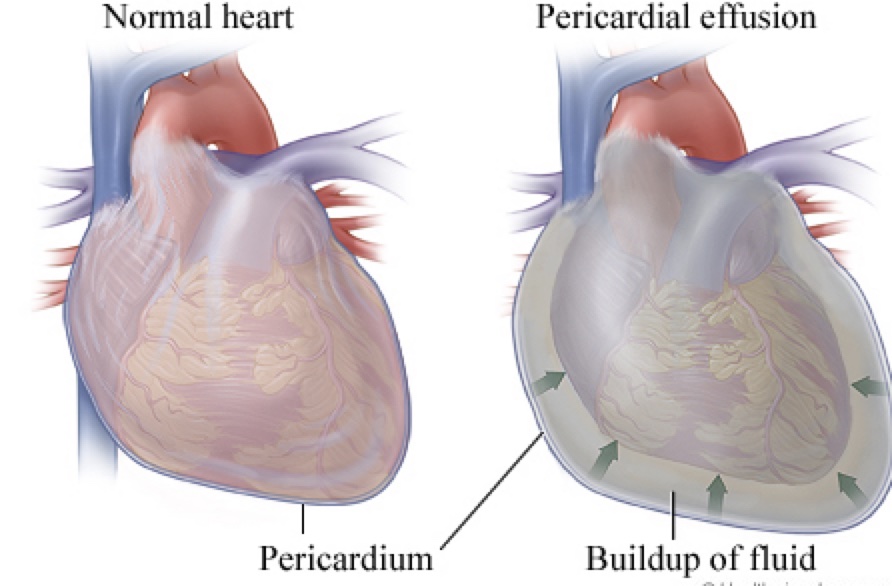

Pericardial effusion is said to develop when there is an excess and abnormal pericardial fluid in the pericardial space. The pericardial disease remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality, with a complex spectrum of no symptoms to severely symptomatic and life-threatening situations.

Knowledge of what a normal pericardium looks like will help us understand the presenting symptoms, clinical findings, diagnosis and effective clinical management.

The Normal Pericardium

The pericardium is a fibrous sac, normally less than 2mm thick that encloses the heart and the great vessels. It keeps the heart in a stable location in the mediastinum, facilitates its movements and separates it from the lungs and other surrounding structures.

The pericardium consists of two layers viz

- The parietal

- The visceral-This covers the surface of the heart.

Between these 2 layers, is a potential space that is filled with a small amount of fluid called the pericardial fluid (usually between 10- 50 mls). This resembles an ultrafiltrate of plasma and it limits the heart’s motions while providing a lubricated slippery surface for the heart to beat inside and the lungs to move outside. It is produced by the mesothelial cells of the visceral layer of the pericardium.

The pericardium also prevents the excessive dilatation of the heart and in a pathological state, prevents overfilling of the heart, which would result in low cardiac output.

What is Pericardial Effusion?

It is a common finding in clinical practice either as an incidental finding or a manifestation of systemic or cardiac disease. The spectrum of pericardial effusions ranges from mild asymptomatic effusions (without symptoms) to cardiac tamponade (Acute heart failure due to compression of the heart by a large or rapidly developing effusion)

Moreover, pericardial effusion may accumulate slowly or suddenly. This condition is very common in developing countries, where tuberculosis is a leading cause of pericardial disease and concurrent HIV infection may also have an important promoting role.

The following mechanism of pleural effusion aetiology has been studied

-

Inflammatory process

The pathological process usually causes an inflammatory process with the possible increased production of pericardial fluid (exudates).

-

Decreased reabsorption

An alternative mechanism of the formation of pericardial fluid may be the decreased reabsorption due to increased systemic venous pressure generally as a result of congestive heart failure or pulmonary hypertension (transudate)

So pericardial effusion leads to increased pericardial pressure which leads to the overcoming of ventricular fillings which leads to decreased stroke volume which finally leads to reduced cardiac output (COP).

Classification of Pericardial Effusion

Pericardial effusion may be classified based on:

-

Its onset

-

- Acute- less than 1 week

- Subacute- more than 1 week but less than 3 months.

- Chronic when dating for more than 3 months.

-

Size

-

- Mild – less than 10mm

- Moderate –between 10-20 mm

- Large- More than 20mm

-

Distribution

-

- Circumferential

- Lobulated

-

Haemodynamic impact

-

- Without cardiac tamponade

- With Cardiac tamponade.

- Effusive-constrictive.

-

Composition / type

-

- Exudates(fluids with a higher protein concentration)

- Transudates( fluids with a lower protein concentration)

- Blood (Haemopericardium)

- Pyopericadium (Pus)

- Pneumo-pericardium(Air)

Causes of Pericardial Effusion

A wide variety of aetiologic agents may be responsible for pericardial effusions.

-

Infections

These could be due to viral, bacterial, and especially tuberculosis infections.

-

Non Infections

-

- Cancers

-

-

- Primary Tumour

-

Pericardial mesothelioma(a very rare cancer that affects the lining of the pericardial sac)

-

-

- Secondary Tumours

-

Lung, breast cancer, lymphomas, and melanoma

-

- Autoimmune diseases like SLE,Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis

- Pericardial injury syndromes (post-myocardial infarction effusions, post-pericardiotomy syndromes, post-traumatic pericarditis either iatrogenic or not),

- Metabolic causes

-

-

- Hypothyroidism.

- Renal failure.

-

-

- Myopericardial diseases

-

-

- Pericarditis.

- Myocarditis,

- Heart failure

-

-

- Aortic diseases

-

-

- Aortic dissection extending into the pericardium,

- Hydro-pericardium, a non-inflammatory transudative pericardial effusion, may occur in heart failure, but also in advanced hypoalbuminaemia, such as in cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome.

-

-

- Trauma

-

-

- Direct Injury (penetrating thoracic injury, oesophageal perforation, and iatrogenic)

- Indirect injury (non-penetrating thoracic injury.

-

-

- Radiation

- Drugs and toxins (rare):

-

-

- Procainamide.

- Hydralazine.

- Isoniazid, and phenytoin (lupus-like syndrome),

- Penicillins (hypersensitivity pericarditis with eosinophilia),

- Doxorubicin and daunorubicin (often associated with cardiomyopathy, may cause a pericardiopathy).

- Minoxidil.

- Immunosuppressive therapies (e.g. methotrexate, cyclosporine)

-

-

- Hemodynamic (heart failure, severe pulmonary hypertension, and hypoalbuminaemia

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms of Pericardial Effusion

The clinical presentation of pericardial effusion is varied according to the speed of pericardial fluid accumulation as mentioned in the introduction, and the aetiology of the effusion with possible symptoms that may be related to the causative disease.

The rate of pericardial fluid accumulation is critical for clinical presentation. If the pericardial fluid is quickly accumulating such as for wounds or iatrogenic perforations, the evolution is dramatic and only small amounts of blood are responsible for a quick rise of intrapericardial pressure and overt cardiac tamponade in minutes.

On the contrary, a slowly accumulating pericardial fluid allows the collection of a large effusion in days to weeks before a significant increase in pericardial pressure becomes responsible for symptoms and signs.

Classical symptoms include

- Dyspnoea on exertion progressing to orthopnoea. (Breathless at rest progressing to breathlessness on lying supine)

- Chest pain, and/or fullness- relieved by sitting up and leaning forward

- Lightheadedness, syncope.

- Cough

- Hoarseness

- Anxiety and confusion.

- Hiccups.

On Clinical examination

- The classical findings of cardiac tamponade have been described by the thoracic surgeon Beck popularly known as the Beck as a triad including:

-

- Hypotension (Low Blood Pressure)

- Acute cardiac tamponade is usually associated with low blood pressure (<90 mmHg) but maybe only be slightly reduced in sub-acute, chronic tamponade

- Hypertensive patients may have normal to mildly elevated blood pressure concomitant to cardiac tamponade.

- Increased jugular venous pressure.

- A small and quiet heart or muffled heart.

- Hypotension (Low Blood Pressure)

- Pulsus paradoxus(exaggerated fall in a patient’s blood pressure during inspiration) and diminished heart sounds on cardiac auscultation.

- Pericardial friction rubs are rarely reported, they can be usually detected in patients with concomitant pericarditis (Rubs are generated by the friction between the two inflamed layers of the pericardium).

- Tachycardia and Tachypnoea

- Fever is a non-specific sign that may be associated with pericarditis either infectious or immune-mediated (i.e. systemic inflammatory diseases).

- Dullness to percussion beneath the angle of the left scapula from compression of the left Lung by pericardial effusion(Ewart sign)

Investigations on the pericardial fluid

- Pericardial fluid analysis (Diagnostic and therapeutic)

-

- Specific gravity> 1015,

- Protein level >3 g/dL

- LDH >200 mg/dL (lactate dehydrogenase)

- Glucose,

- Blood cell count

- Biomarkers. Tumour markers (i.e. CEA >5 ng/mL or CYFRA 21-1 >100 ng/mL)

- PCR for specific infectious agents (i.e. TBC).

- Acid-fast bacilli staining, mycobacterium cultures, aerobic, and anaerobic cultures.

- Baseline investigations

-

- Complete blood count

- Electrolytes

- Cardiac enzymes

- Thyroid profile

- Rheumatic factor, Immunoglobulin complexes and antinuclear Ab test

- CT-scan and MRI

- Cx Ray- water bottle configuration is noted.

Diagnosis of Pericardial Effusion

When the pericardial effusion is detected, the first step is to evaluate its size and haemodynamic importance, as well as the possible association with concomitant diseases.

- Echocardiography is the first diagnostic tool for this assessment.

- Computed tomography (CT) or cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) may confirm the finding in specific cases.

Please note that after pericardial scarring (i.e. after cardiac surgery or chronic pericarditis, or bacterial infections), pericardial fluid may not have a uniform distribution within the pericardial space and may give rise to loculated effusions that should be evaluated with multiple cardiac views.

Treatment of Pericardial Effusion

- Watchful waiting

A truly isolated effusion may not require a specific treatment if the patient is asymptomatic, but large ones are at risk of progression to cardiac tamponade.

- Oxygen supplementation.

- Fluid restriction.

- Bed rest with leg elevation.

- Drug treatment

-

- Aspirin or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

- Colchicines

- Steroid

- Antibiotics-ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin

- Pericardiocentesis (if the patient is unstable).

Large effusions may receive a diagnostic pericardiocentesis to evaluate the aetiology or causes or drained to provide symptomatic relief if the patient has associated symptoms such as dyspnoea, chest discomfort, pulmonary or lower extremity oedema, or decreased exercise tolerance.

The type of intervention chosen is based on the aetiology of the pericardial effusion, the clinical status of the patient at the time of the intervention, and the patient’s expected clinical course. It is mandatory for cardiac tamponade and when bacterial or neoplastic aetiology is suspected.

Effusions that have accumulated rapidly enough or have grown to such a size as to cause hemodynamic instability or collapse are managed as emergencies at the bedside, the cardiac catheterization lab, or the operating room.

Techniques for drainage of pericardial effusion include

- Needle pericardiocentesis via subxiphoid or parasternal or apical approach with or without placement of a pericardial drain for serial evacuation.

- Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy.

- Emergency thoracotomy.

- Pericardiotomy.

- Surgical pericardial window via subxiphoid, anterior mini-thoracotomy, or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) approach.

Note, that patients who have large pericardial effusions with underlying ventricular dysfunction have the risk of developing pericardial decompression syndrome (PDS) after pericardiocentesis. Pericardial decompression syndrome (PDS) is an infrequent, life-threatening condition.

If tamponade or pericardial effusion is recurrent the following can be done Viz

- Pericardial Sclerosis

-

- Tetracycline, doxycycline, cisplatin or 5 Fluorouracil can be used

- Pericardio-Peritoneal shunt

- Pericardiectomy

Prognosis and Outcome

The prognosis of pericardial effusion is essentially related to the causes and, thus, it is important to identify specific causes that require targeted therapies.

Bacterial aetiologies as well as post-radiation pericardial diseases, and pericardial injury syndromes have an increased risk of developing complications.

Idiopathic pericardial effusion and pericarditis have an overall good prognosis with a very low risk of complications.

Large idiopathic chronic effusion (>3 months) has a 30–35% risk of progression to cardiac tamponade.

The follow-up of pericardial effusion is mainly based on the evaluation of symptoms and the echocardiographic size of the effusion as well as additional features such as inflammatory markers (i.e. C-reactive protein).

It is recommended to tailor the follow-up to the aetiology, adopted therapies (usually a control after 1–2 weeks and then after 1 month and 6 months), and monitor the possible evolution towards worsening pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and constrictive pericarditis. For idiopathic moderate effusions, appropriate timing for echocardiographic follow-up may be an echocardiogram every 6 months. For a severe effusion, an echocardiographic follow-up maybe every 3–6 months.

Complications

- Tamponade

- Free wall rupture.

In this setting, urgent surgical treatment is life-saving. However, if the immediate surgery is not available or contraindicated, pericardiocentesis and intrapericardial fibrin-glue instillation could provide an alternative immediate treatment.

- The most serious complications of pericardiocentesis are laceration and perforation of the myocardium and the coronary vessels.

- In addition, patients can experience air embolism, pneumothorax, arrhythmias (usually vasovagal bradycardia), and puncture of the peritoneal cavity or abdominal viscera.

- Internal mammary artery fistulas, acute pulmonary oedema, and purulent pericarditis were rarely reported.

The safety was improved with echocardiographic or fluoroscopic guidance.

Conclusion

Pericardial effusion is a common finding in clinical practice either as an incidental finding or a manifestation of systemic or cardiac disease. The spectrum of pericardial effusions ranges from mild asymptomatic effusions to cardiac tamponade.

The aetiology is varied (infectious, neoplastic, autoimmune, metabolic, and drug-related), being tuberculosis the leading cause of pericardial effusions in developing countries and all over the world, while concurrent HIV infection may have an important promoting role in this setting.

Management is guided by the haemodynamic impact, size, presence of inflammation (i.e. pericarditis), associated medical conditions, and the aetiology whenever possible.