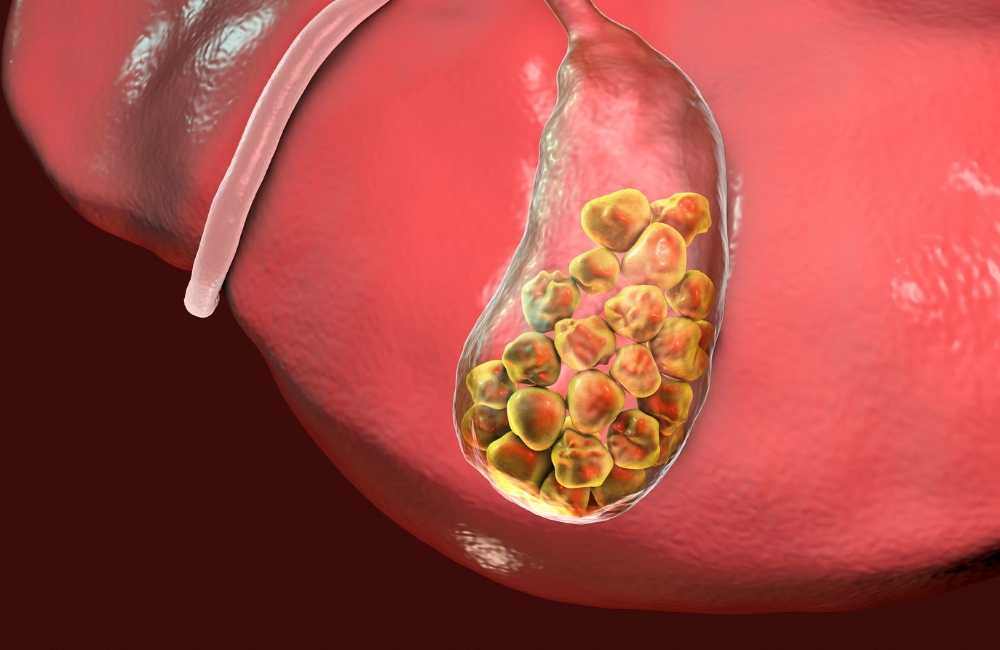

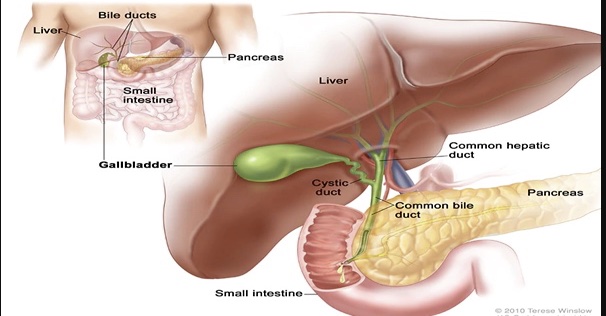

Gallstones, also known as cholelithiasis, are the presence of one or more gallstones in the gallbladder. The gallbladder is a pear-shaped organ located on the right upper side of the abdomen below the liver and measures approximately 7 cm to 10 cm in length and 4 cm in width.

Even though the organ is small, it is a common cause of abdominal pain due to gallstones. The function of the gallbladder is to store bile (3l to 50 ml), which is released during the digestive and absorptive processes in the intestine.

Contraction of the gallbladder with the release of bile into the biliary tree and duodenum is caused by gastric distension and fatty food content. This stimulates the secretion of cholecystokinin (CCK) from inclusion cells of the duodenum which causes contraction of the gallbladder.

Disruption of neuro innervation, blockage of the cystic duct from gallstones, or other etiologies can cause symptoms of chronic or acute cholecystitis. Tests such as a nuclear HIDA (hepatobiliary) scan with CCK, or ultrasound are used to diagnose gallbladder disease.

The liver produces bile and stores them in the gallbladder (storage capacity of between 30 to 50 mls). The function of the gallbladder is bile storage/concentration and release of bile into the duodenum when required especially during digestive and absorptive processes.

The bile concentration function is done by active absorption of water, sodium chloride and bicarbonate by the mucous membrane of the gallbladder thus making the hepatic bile 5–10 times concentrated with a corresponding increase in the proportion of bile salts, bile pigments, cholesterol and calcium.

When there is fatty food content or gastric distention, the duodenum secretes a hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK) which causes the gall bladder to contract and discharge its contents. It also secretes mucus of about 20mls/day. When the bile precipitates, they harden and form ‘stones’ called gallstones.

What are Gallstones?

Gallstones, also known as cholelithiasis, are the presence of one or more gallstones in the gallbladder. Biliary sludge is often a precursor of gallstones.

It consists of calcium bilirubinate (a polymer of bilirubin), cholesterol microcrystals, and mucin. Sludge develops during gallbladder stasis, as occurs during pregnancy or the use of total parenteral nutrition. Most sludge is asymptomatic and disappears when the primary condition resolves. However, sludge can evolve into gallstones or migrate into the biliary tract, obstructing the ducts and leading to biliary colic.

Gallstones are solid masses formed when bile precipitates. These “stones” may occur in the gallbladder or the biliary tract (ducts leading from the liver to the small intestine). There are two types of gallstones:

-

Cholesterol stones

Cholesterol stones are yellow-green and are primarily made of hardened cholesterol. They are predominantly found in women and obese people and are associated with bile supersaturated with cholesterol. They account for 80% of gallstones and are more commonly involved in obstruction and inflammatory reactions.

-

Pigment stones

Pigment stones may be black or brown stone or mixed viz:

-

- Black Pigment Stones

Black pigment stones are made of pure calcium bilirubinate or complexes of calcium, copper, and mucin glycoproteins.

They are more likely to remain in the gallbladder.

-

- Brown stones

Brown pigment stones are composed of calcium salts of unconjugated bilirubin and with small amounts of cholesterol and protein. These stones are often located in bile ducts causing obstruction and are usually found in conditions where there is infected bile.

Gallstones grow at about 1 to 2 mm/year, taking 5 to 20 years before becoming large enough to cause problems. Most gallstones form within the gallbladder, but brown pigment stones form in the ducts. Gallstones may migrate to the bile duct after cholecystectomy or particularly in the case of brown pigment stones, develop behind strictures as a result of stasis and infection.

Risk Factors for Developing Gallstones

Some risk factors for gallstones related to diet are modifiable, while other factors are not. Unmodifiable risk factors are things like age, race, sex, and family history.

-

Lifestyle risk factors

-

- Living with obesity.

- A diet that is high in fat or cholesterol and low in fibre.

- Undergoing rapid weight loss.

- Living with type 2 diabetes.

-

Genetic risk factors

-

- Being born female.

- Being of Native American or Mexican descent.

- Having a family history of gallstones.

- Being 60 years or older.

-

Medical risk factors

-

- Living with liver Cirrhosis.

- Being pregnant.

- Taking certain medications to lower cholesterol.

- Taking medications with a high estrogen content (like certain birth controls).

In as much as some medications increase the risk of gallstones, they should not be stopped unless the healthcare provider approves such.

Gallstones Symptoms

In 80% of the cases, no symptoms but patients are presenting with symptoms typically complain of the following:

- Right upper abdomen or epigastric pain, which may radiate to the back. This may be described as colicky, but more often is dull and constant.

- Dyspepsia, flatulence, food intolerance, particularly to fats.

- Some alteration in bowel frequency.

- Biliary colic is typically present in 10–25% of patients. This is described as severe right upper abdominal pain that ebbs and flows associated with nausea and vomiting. Pain may radiate to the chest and is usually severe and may last for minutes or even several hours. Frequently, the pain starts during the night, waking the patient although minor episodes may occur intermittently during the day. Dyspeptic symptoms may coexist and be worse after such an attack.

As the pain resolves, the patient can eat and drink again, often only to suffer further episodes. It is of interest that the patient may have several episodes of this nature over a few weeks and then no more trouble for some months.

Investigations For Gallstones

-

Blood work

-

- Liver function test (LFT)

- Complete blood count (CBC)

-

Imaging

-

- Ultrasonography

Abdominal ultrasonography is the imaging test of choice for detecting gallbladder stones. Sensitivity and specificity are 95%. Ultrasonography also accurately detects sludge.

-

- Cholangiography

A dye is injected into the bloodstream or straight into the bile ducts using an ERCP (Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) it is a procedure that combines an upper GI endoscopy and X-ray, and the dye concentrates into the bile ducts or gallbladder and shows up on X-rays.

-

- CT scan

This is a non-invasive X-ray that produces cross-section pictures of the inside of the human body.

-

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

This is a type of MRI that specifically visualizes the bile ducts. It’s non-invasive and creates very clear images of your biliary system, including the common bile duct. Your provider might use this test first to find a suspected gallstone. But if they’re already pretty sure it’s there, they might skip it and go straight to an ERCP.

-

- Cholescintigraphy or Hepatobiliaryiminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan

A small amount of harmless radioactive material is injected into the patient. This is absorbed by the gallbladder and stimulates it to contract. This test may diagnose abnormal contractions of the gallbladder or obstruction of the bile duct.

Diagnosing Gallstones

The diagnosis of gallstone disease is based on viz:

- History.

- Physical examination.

In the acute phase, the patient may experience a right upper abdominal pain that gets worse during inspiration by the examiner’s right subcostal palpation (Murphy’s sign). A positive Murphy’s sign suggests acute inflammation and may be associated with increased white cell count and moderately elevated liver function tests.

A mass may be palpable as the omentum walls off an inflamed gallbladder. Fortunately, in the majority of cases, this process is limited by the stone slipping back into the body of the gallbladder and the contents of the gallbladder.

If resolution does not occur, pus may develop in the gallbladder and the wall may become necrotic and perforate, with the development of localized peritonitis

- Confirmatory radiological studies such as:

- Trans abdominal ultrasonography

- Hepatobiliaryiminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan.

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

Treatment for Gallstones

-

For asymptomatic stones

Most asymptomatic patients decide that the discomfort, expense, and risk of elective surgery are not worth removing an organ that may never cause clinical illness. Expectant management is done in this situation.

-

For symptomatic stones

If symptoms occur, gallbladder removal (cholecystectomy) is indicated because pain is likely to recur and serious complications can develop.

- Surgery:

Surgery can be done with:

-

- Open cholecystectomy

Open cholecystectomy involves a large abdominal incision and direct exploration. It is safe and effective. Its overall mortality rate is about 0.1% when done electively during a period free of complications.

-

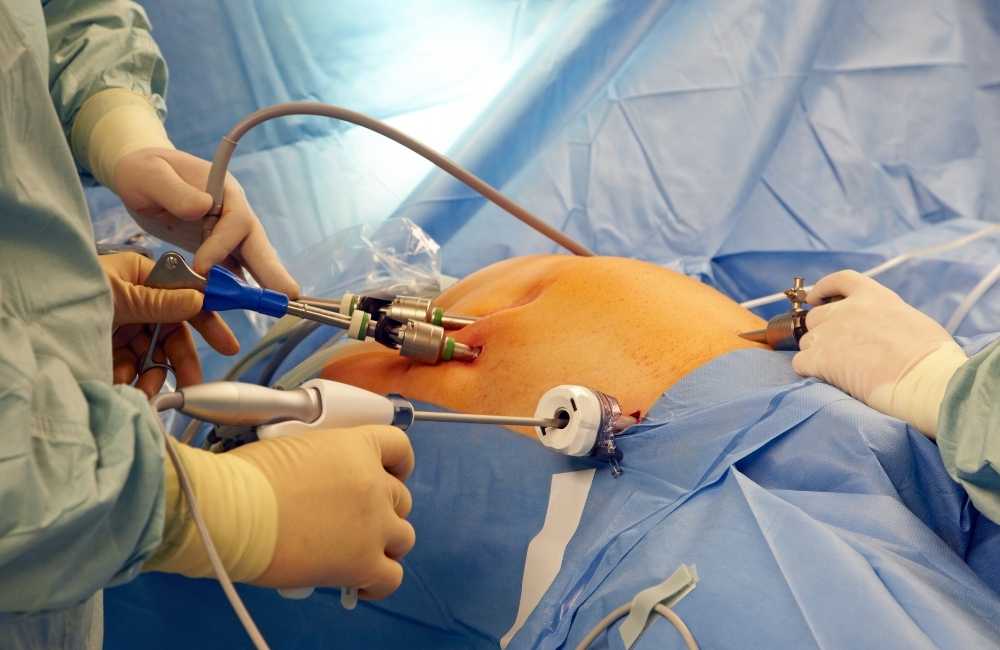

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice. Using video endoscopy and instrumentation through small abdominal incisions the gallbladder is removed. The procedure is less invasive than open cholecystectomy. The result is a much shorter recovery, decreased postoperative discomfort, and improved cosmetic results, yet no increase in morbidity or mortality.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy may be converted to an open procedure in 2 to 5% of patients, usually because biliary anatomy cannot be identified or a complication cannot be managed. Older age typically increases the risks of any type of surgery.

Cholecystectomy effectively prevents future biliary colic but is less effective for preventing atypical symptoms such as dyspepsia. Cholecystectomy does not result in nutritional problems or a need for dietary limitations. Some patients develop diarrhoea, often because bile salt malabsorption in the ileum is unmasked.

Prophylactic cholecystectomy is warranted in asymptomatic patients with cholelithiasis only if they have large gallstones (more than 3 cm) or a calcified gallbladder (porcelain gallbladder) as these conditions increase the risk of gallbladder carcinoma.

-

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

When a person with gallstones cannot have surgery or use ursodeoxycholic acid, they may undergo endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which requires a local anaesthetic. A flexible fibre-optic camera, or endoscope, is passed into the person’s mouth and then passes through the digestive system and into the gallbladder. An electrically heated wire widens the opening of the bile duct and the stones are removed or made to pass into the intestine.

- Non-surgery

- Stone dissolution

For patients who decline surgery or who are at high surgical risk (e.g., because of concomitant medical disorders or advanced age), gallbladder stones can sometimes be dissolved by ingesting bile acids orally for many months. The best candidates for this treatment are those with small, radiolucent stones.

Oral dissolution therapy typically includes using the medications ursodiol (Actigall) and chenodiol (Chenix) to break up gallstones. These medications contain bile acids, which work to break up the stones.

This treatment is best suited for breaking up cholesterol stones and can take many months or years to work completely.

-

- Stone fragmentation (extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy)

A lithotripter is a machine is used. This generates shock waves that pass through a person to break gallstones into smaller pieces.

-

- Percutaneous drainage of the gallbladder

This involves placing a sterile needle into the gallbladder to aspirate (draw out) bile. A tube is then inserted to help with additional drainage. This procedure isn’t typically the first line of defence and tends to be an option for individuals who may not be suited for other procedures.

Complications of Gallstones

Complications of gallstones may include:

-

Inflammation of the gallbladder

A gallstone that becomes lodged in the neck of the gallbladder can cause inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis) and this can cause severe pain and fever.

-

Blockage of the common bile duct

Gallstones can block the tubes (ducts) through which bile flows from your gallbladder or liver to the small intestine. Severe pain, jaundice and bile duct infection can result.

-

Blockage of the pancreatic duct

The pancreatic duct is a tube that runs from the pancreas and connects to the common bile duct just before entering the duodenum. Pancreatic juices, which aid in digestion, flow through the pancreatic duct.

A gallstone can cause a blockage in the pancreatic duct and this can lead to inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis). This causes intense, constant abdominal pain and usually requires hospitalization.

-

Gallbladder cancer

Persons with a history of gallstones have an increased risk of gallbladder cancer. Although this is very rare, even though the risk of cancer is elevated, the likelihood of gallbladder cancer is still very small.

Conclusion

Anyone who has occasional signs or symptoms of gallstones should speak with their doctor. If their symptoms are persistent or severe, should visit the local emergency room for more urgent evaluation and treatment. Anyone with gallstones or choledocholithiasis needs prompt medical attention to limit complications.