Cancer of the prostate (CAP) is the adenocarcinoma of the prostate gland. Cancers are unregulated proliferation or multiplication of cells with the following prominent properties viz

- A lack of cell differentiation.

- Local invasion of adjoining tissue.

- Spread to distant sites through the bloodstream or the lymphatic system (Metastasis).

When this happens in the prostate, cancer of the prostate (CAP) results, although, the immune system may play a role in eliminating early cancers or premalignant cells. This concept is termed immune surveillance.

Prostate cancer remains the most common malignancy affecting men and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in men in the world.

Adenocarcinoma (cancer that develops in the glands that line the organs) accounts for about 95% of prostatic cancers and frequently it has no specific presenting symptoms. More often than not, CAP is clinically silent, although it sometimes mimics obstructive symptoms of benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH).

Therefore, patients may be diagnosed with advanced CAP with metastases without symptoms related to the region of the prostate. Consequently, the diagnostic value of patient screening by using early detection programs has come to the forefront of focus.

With the introduction of widespread screening with serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA), the incidence of late-stage presentation has dramatically lessened, although with an increased number of CAPs detected.

PSA is an enzyme (serine protease) secreted by prostatic epithelium that aids the liquefaction of the ejaculate by lysing seminal vesicle proteins. However, the main clinical use is as a tumour marker specific for CAP.

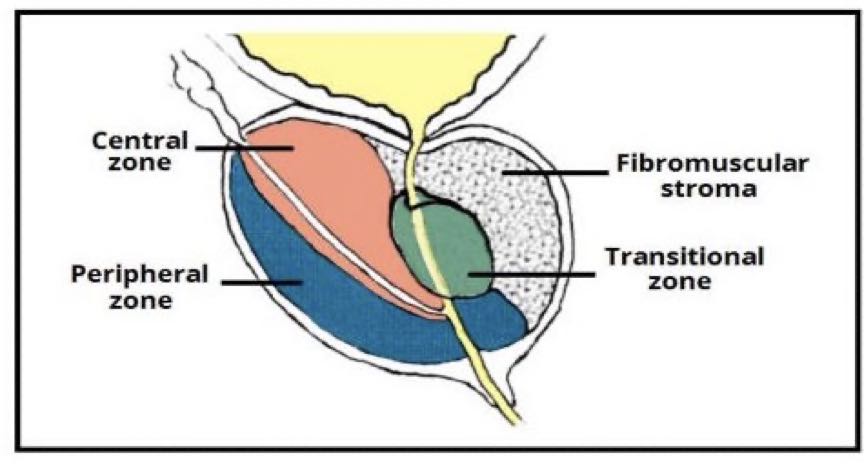

To understand the cancer of the prostate, a little knowledge of the surgical anatomy of the prostate is important.

Anatomy of the prostate

The prostate is a walnut-sized gland that arises from the primitive urethra as early as 9 weeks in utero (in the uterus before birth), found in men as part of the reproductive system and is located under the urinary bladder and surrounds the urethra with a weight of about 20g and measures 3 by 4 by 2 cm.

This is only found in Men, though the skin’s gland is a homologue in females. The prostate helps make semen, which carries sperm. It does this in conjunction with other accessory glands (Seminal vesicles and the bulbourethral gland also called the Cowper’s gland.

Sperms cells + Secretions from these glands = Semen

The prostate is histologically divided into 3 zones viz:(see the diagram above)

-

Central zone

Surrounds the ejaculatory ducts, comprising approximately 25% of normal prostate volume.

-

Transitional zone

Located centrally and surrounds the urethra, comprising approximately 5-10% of normal prostate volume. The glands of the transitional zone are those that typically undergo benign hyperplasia (BPH).

-

Peripheral zone

Makes up the main body of the gland (approximately 65%) and is located posteriorly. There is an increased incidence of acute and chronic inflammation found in these compartments, a fact that may be linked to the high cases of prostate carcinoma in the peripheral zone.

The peripheral zone is also the area felt against the rectum on rectal examination.

-

The fibro muscular stroma (or “fourth zone”)

The fibro muscular stroma is situated anteriorly in the gland. It merges with the tissue of the urogenital diaphragm.

What is Cancer of the Prostate (CAP)?

Cancer of the prostate (CAP) usually refers to the adenocarcinoma of the prostate gland. Sarcoma of the prostate is rare, occurring primarily in children. Undifferentiated prostate cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, and ductal transitional carcinoma also occur infrequently. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) is considered a possible premalignant histologic change.

Incidence increases with each decade of life; autopsy studies show prostate cancer in 15 to 60% of men aged 60 to 90 years old, with incidence increasing with age.

The lifetime risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer is 1 in out of every 6 Men. The median age at diagnosis is 72, and more than 75% of prostate cancers are diagnosed in men more than 65 years of age. Risk is highest for Black men.

Symptoms of Cancer of the Prostate

Prostate cancer usually progresses slowly and rarely causes symptoms until advanced. In advanced disease, the following symptoms are observed:

- Passage of bloody urine (hematuria).

- Symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction or Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

-

- Straining.

- Acute urine retention.

- Hesitancy.

- Poor flow (unimproved by straining)

- Weak or intermittent urine stream (stops and starts)

- A sensation of incomplete or poor bladder emptying.

- Terminal dribbling (including after urination).

- Frequency.

- Nocturia.

- Urgency.

- Urge incontinence.

- Nocturnal incontinence.

- Ureteral obstruction.

-

- Renal colic.

- Flank pain.

- Renal dysfunction.

- Bone pain, pathologic fractures, or spinal cord compression may result from osteoblastic metastases to bone (commonly to the pelvis, ribs, and vertebral bodies).

Investigations for Cancer of the Prostate

-

Complete blood count

There may be anaemia secondary to extensive marrow invasion, or secondary to renal failure. There may also be low platelet count (thrombocytopenia) and evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC)

-

Liver function tests

These will be abnormal if there is an extensive metastatic invasion of the liver. The alkaline phosphatase may be raised from either hepatic involvement or spread in the bone. These can be distinguished by the measurement of isoenzymes or gamma-glutamyltransferase. (y-GT)

-

Prostatic specific antigen (PSA)

It is good at following the course of advanced disease. It is lacking in sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of early-localized prostate cancer. Nevertheless, the finding of a PSA > 10 nmol ml–1 is suggestive of cancer and > 35 ng ml–1 is almost diagnostic of advanced prostate cancer. A decrease in PSA to the normal range following hormonal ablation is a good prognostic sign.

-

Acid Phosphates

Acid phosphatase has been superseded by the measurement of PSA.

-

Radiological examination

Radiographs of the chest may reveal metastases in either the lung fields, the ribs, the lumbar vertebrae or the pelvic bones. The bone appears dense and coarse.

-

Bone marrow aspiration

Sometimes, examination of the bone marrow will reveal the presence of metastatic carcinoma cells.

Diagnosing Cancer of the Prostate

- Incidental diagnosis

Occasionally, prostate cancer is diagnosed incidentally in tissue removed during surgery for benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH).

- The rectal examination also called digital rectal examination (DRE)

Sometimes stony-hard induration or nodules are palpable during DRE. Induration and nodularity suggest cancer but must be differentiated from prostate calculi.

Extension of induration to the seminal vesicles and lateral fixation of the gland suggest locally advanced prostate cancer

- Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)

TRUS may be used to access the local stage and can be combined with a prostate biopsy.

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

PSA Screening is commonly done annually in men older than 50 years old but is sometimes begun earlier for men at high risk (e.g., those with a family history of prostate cancer and Black men.

The likelihood of cancer increases with increasing PSA levels, there is no cut-off below which there is no risk.

- Biopsy of the prostate or biopsy of metastatic lesion

If there is suspicion of prostate cancer, because of local findings, a raised PSA or metastatic disease, then a transrectal biopsy using an automated gun is recommended. Routine local anaesthetic is used to decrease pain. About 10 systematic biopsy cores are obtained as well as a biopsy of any suspicious areas. Broad- spectrum broad-spectrum antibiotic cover is given to all patients to reduce the incidence of sepsis.

- Grading by histology

Grading helps define the aggressiveness of the tumour. The Gleason score is commonly used. The Gleason score helps predict the likelihood of capsular penetration, seminal vesicle invasion, and spread to lymph nodes.

- Staging by CT/MRI and bone scanning, possibly prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)–based PET CT

Multi-parametric MRI can risk-stratify patients for the need for a biopsy and identify suspect areas that should be targeted. It is now used before initial biopsy in men with a prior negative biopsy or in men who are on active surveillance.

- Urinary prostate cancer antigen 3 [PCA-3], Prostate Health Index, 4Kscore, urinary Select MDX

Treatment for Cancer of the Prostate

Treatment is guided by:

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level.

- Grade and stage of the tumour.

- Age of the patient.

- Coexisting disorders.

- Life expectancy.

- Patient’s preferences.

The goal of therapy can be

- Active surveillance

Active surveillance is appropriate for many patients without symptoms or with low-risk, or possibly even intermediate-risk, localized prostate cancer or if life-limiting disorders coexist. Here, the risk of death due to other causes is greater than that due to prostate cancer.

This approach requires periodic digital rectal examination (DRE), PSA measurement, and monitoring of symptoms.

- Definitive treatment or Local Therapy for Cancer of the Prostate

Therapy is aimed at curing prostate cancer viz

-

Radical prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy (removal of prostate with seminal vesicles and regional lymph nodes) is probably best for patients less than 75 years old with a tumour confined to the prostate.

-

Radiation therapy

3-dimensional radiation therapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), which safely deliver doses approaching 80 greys (Gy) to the prostate.

Newer forms of external radiation therapy such as proton therapy are more costly, and the benefits in men with prostate cancer are not established.

Brachytherapy involves the implantation of radioactive seeds into the prostate through the perineum. These seeds emit a burst of radiation over a finite period (usually 3 to 6 months) and are then inert.

-

Cryotherapy for treating cancer of the prostate

Cryotherapy (destruction of prostate cancer cells by freezing with cryoprobes, followed by thawing) is less well established; long-term outcomes are unknown. This may be used if radiation therapy is unsuccessful.

-

HIFU (high-intensity focused ultrasound)

This uses intense ultrasound energy administered transrectally to ablate prostate tissue. It has been used for many years in Europe and Canada and has recently become available in the US. The role of this technology in the management of prostate cancer is evolving; presently, it appears to be best suited for radiation-recurrent prostate cancer.

-

Systemic methods for treating cancer of the prostate

This method is aimed at decreasing or limiting tumour extent) and extending quantity and quality of life. If cancer has spread beyond the prostate gland, the cure is unlikely; systemic treatment aimed at decreasing or limiting tumour extent is usually given.

- Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)

Hormonal influences contribute to the course of adenocarcinoma but almost certainly not to other types of prostate cancer. Androgen deprivation is thus archived by castration (surgically by bilateral orchiectomy or medically) with:

-

- Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists such as leuprolide, goserelin and buserelin. LHRH agonists may cause PSA levels to increase temporarily.

- LHRH antagonists (eg, degarelix) can also lower the testosterone level, usually more rapidly than LHRH agonists.

Cancer that progresses (indicated by an increasing PSA level) despite a testosterone level consistent with castration (< 50 ng/dL [1.74 nmol/L]) is classified as castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

- Androgen-receptor targeted therapies (abiraterone acetate with prednisone, enzalutamide or chemotherapy (with docetaxel) can be given in combination with androgen deprivation therapy, although the choice of therapy is determined by the volume of metastatic disease and patient comorbidities.

- Combined androgen blockade.

- Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists plus anti-androgens.

Total androgen ablation is given until PSA levels are reduced (usually to undetectable levels), then stopped. Treatment is started again when PSA levels rise above a certain threshold, although the ideal threshold is not yet defined.

Treatment summary

- For localized cancer within the prostate, surgery, radiation therapy, or active surveillance.

- For cancer outside of the prostate, palliation with hormonal therapy, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy.

- For some men who have low-risk cancers, active surveillance without treatment is.

Conclusion

Prostate cancer is usually an adenocarcinoma and progresses slowly and rarely causes symptoms until advanced causing blood in the urine or lower urethral tract symptoms (LUTS).

Diagnosis is by digital rectal examination, Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurements and confirmed by trans rectal guided ultrasound biopsy.

Screening using PSA is controversial and should involve shared decision-making. The cancer detection rate using the measurement of PSA is between 2% and 4%, and approximately 30% of men with an elevated PSA will have prostate cancer confirmed by biopsy.

Unfortunately, 20% of men with clinically significant prostate cancer will have PSA values within the normal range. There is therefore controversy over the usefulness of PSA alone as a screening procedure. The prognosis for early cancer of the prostate is very good.

Be informed about the test, the risks of the prostate biopsy that might be required and the risks of the detection of cancer that we are not certain how best to treat, as well as the positive aspects of the early discovery of small prostate cancer.